Holocaust Memorial Day, January 29th. A small group gather to commemorate the victims of the Shoah in front of the Memorial to Resistance, Como.

On 22nd February 1944, a train left Fossoli concentration camp near the town of Carpi in the Province of Modena with 650 people on board. Its destination was Auschwitz. It arrived there four days later on 26th February. 525 of its passengers were immediately marched on their arrival to the newly constructed gas chambers where they were killed. The remaining 125 were deployed as slave labour. Out of their number only five survived to return back to Italy. This train, named as Convoy 8, was the first of a further five convoys from Fossoli sending Jews to the Nazi death camps.

Convoy 8 included a number of men, women and children who had been arrested, interrogated or detained in Como and then sent on to Fossoli. Most had moved to within the province either to escape the allied bombing of Milan or to try to reach salvation across the Swiss border. The majority were Italian citizens. They were all captured by agents of the fascist state – the Polizia di Stato (PS), the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana (GNR), or the Border Militia particularly the ‘Monte Rosa’ legion.

Enemies of State

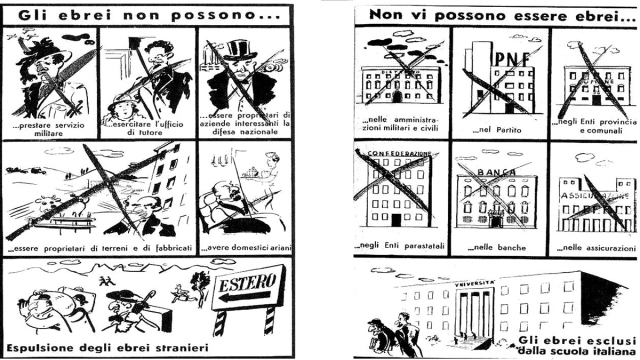

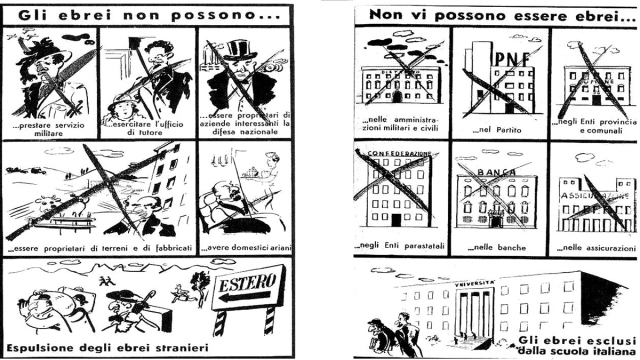

Italian fascism had not adopted antisemitism as a fundamental element of its ideology at birth unlike Nazism. It had though shown its propensity for racism before and during the conflict with Ethiopia. However Jews had remained socially integrated and, in the majority of cases, fully supportive of the regime in its early years. All was to change in 1938 when Mussolini introduced the first of his race laws depriving Italian Jews of key rights and limiting the freedom of those foreign Jews who had migrated from Germany or other Nazi-occupied territories. Along with a variety of restrictions to civic rights, the law now required all Jews to register their ethnicity with their local state police.

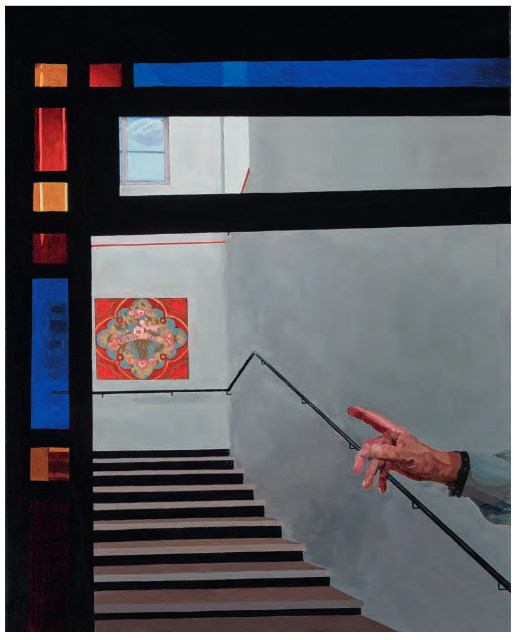

The Questura di Como, State Police. From 1938 all citizens of Jewish descent had to declare their ethnicity at the local Questura.

In June 1940 a government decree forced foreign Jews into internment camps. The largest of the fifteen specially constructed camps was at Ferramonti di Tarsia in Calabria. It held 2,700 internees at its peak in the summer of 1943. These were to prove the more fortunate in that they were liberated by allied forces in September of that year. This was also the month in which the Nazis occupied the north and centre of the country and re-established Mussolini as head of the so-called RSI (Repubblica Socialista Italiana). From that date the lives of all Jews living within the nazifascist occupied territory were at risk.

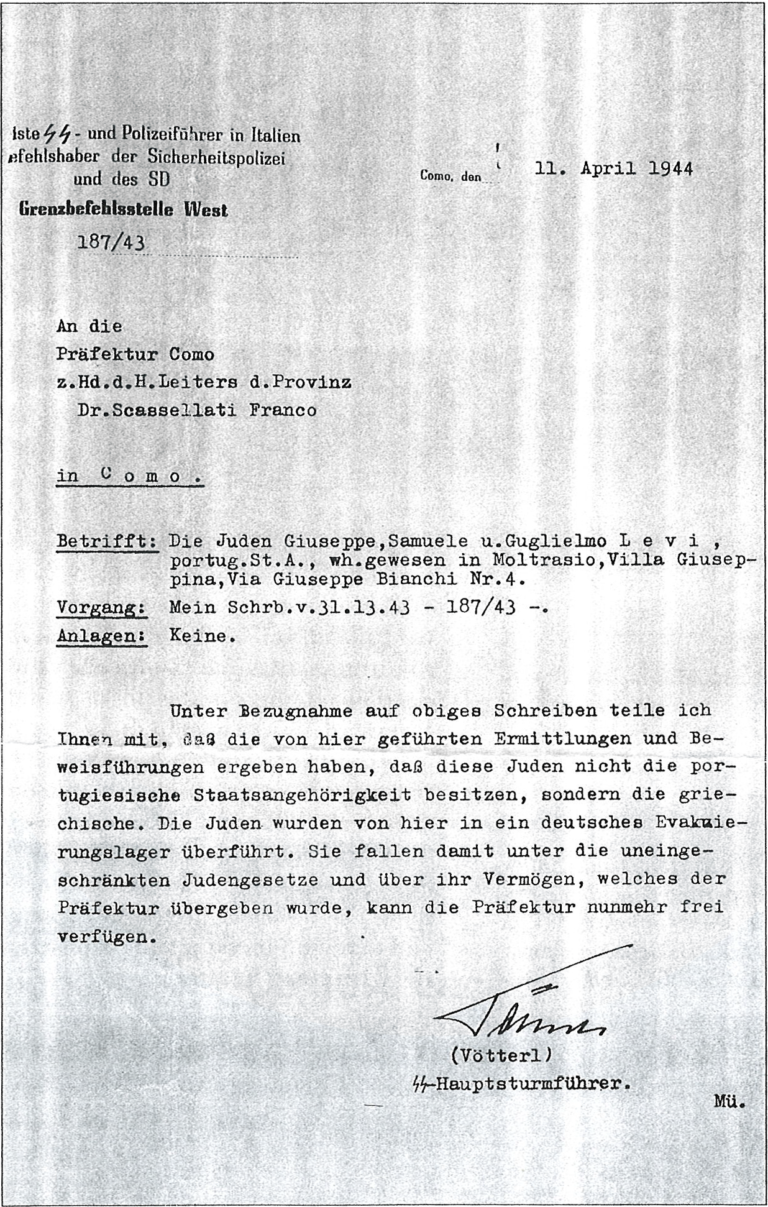

A law was passed on 14th November 1943 defining all Jews as foreigners. Sixteen days later it was decreed that all Jews of whatever nationality were to be treated as enemies of the state and as such, to be arrested and interned. All of the various repressive agencies of the RSI were authorised to arrest Jews and seize their property and possessions. The Italian state then handed over their prisoners to the Nazis who organised their transport into slavery, or more frequently, execution.

Using stereotypical caricature, this Nazifascist poster summarises the restrictions imposed by Mussolini’s 1938 Race Laws.

The Bid to Escape

During the very first days of the Nazi occupation, thousands sought to cross the border into Switzerland at Ponte Chiasso. They included Jews, allied ex-prisoners of war and demobbed Italian soldiers. The Nazis took immediate steps on arriving in Como on September 12th 1943 to close and control the border. This drove those seeking safety to adopt clandestine routes over the mountains as habitually used by local smugglers.

The De Benedetti family, photo courtesy of CDEC.

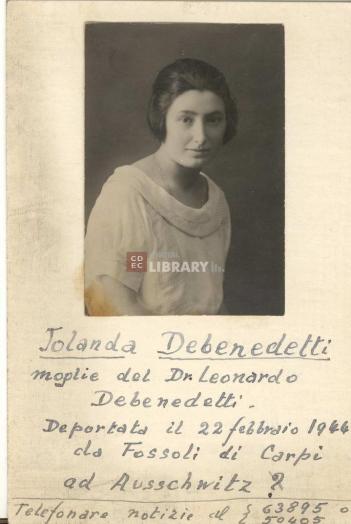

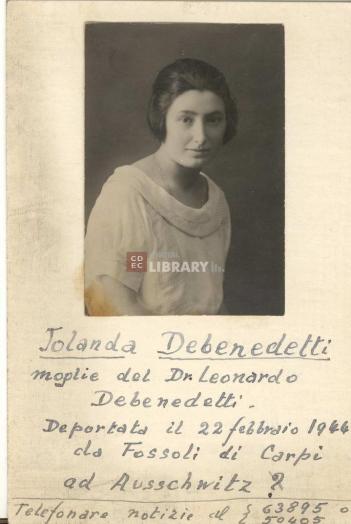

Leonardo De Benedetti, a 45 year old medical doctor from Turin, had crossed over the Swiss border below Lanzo D’Intelvi on 3rd December 1943. He had been accompanied by his mother, wife and other members of the family. The Swiss had allowed his elderly mother and other family members to stay but forced Leonardo and his wife Jolanda back over the border, leading to their immediate arrest. Husband and wife were detained in Como and then moved to the newly opened concentration camp in Fossoli. They were both then put on Convoy 8 leaving Fossoli for Auschwitz on 22nd February 1944.

The wire fence marks the Italian Swiss border above Maslianico on the side of Monte Bisbino with a now disused guard hut on the Italian side. Escapees were led to areas such as this where they sought safety through gaps in the wire fencing. This form of escape would not be suitable for a family travelling with a new-born child.

The start of December saw the arrest of a number of families trying to cross the border. All those listed here were to find themselves detained in Como and then moved to Fossoli to be placed on Convoy 8 leaving for Auschwitz on February 22nd 1943. They included the Bassani family from Venice arrested on 1st December. The family consisted of father Edgardo aged 50, mother Nives, aged 43, son Franco aged 20 and daughter Tina aged 14.

Franco Bassani (Number 7). Photo courtesy of CDEC

The Valabrega family from Genoa consisting of father Arturo, 49, mother Ida, 59 and son Luciano 22 were also arrested on 1st December trying to cross the border.

The Calò family were arrested in Olgiate Comasco on 2nd December. The family was originally from Trieste and consisted of father Emilio, aged 59, wife Enrichetta, aged 51, daughter Rosina aged 21 and son Giuseppe aged 20. They were also accompanied by Enrichetta’s brother, Vittorio aged 49 from Venice and his wife Norma aged 44.

Enrichetta Gentilli, mother to Rosina and Giuseppe

The six members of the Calò family had travelled over from Trieste with the Campi family. The Campi family were arrested on 3rd December. They were Massimiliano, born in Poland but resident in Trieste, aged 57, his wife Iris aged 40 and their daughter Lia Anna aged 14.

Both the Calò and Campi families had entrusted themselves to a group organising clandestine crossings into Switzerland run by the owners of the ‘Volta’ bar in Brunate – Primo Massa and his wife. Massa’s band provided at a price foreign exchange and guided passage over the border to Jews, ex prisoners of war and other refugees. His group had been infiltrated by a ruthless hunter of Jews and partisans called Gaddo Jermini who worked in the state police directly for the Prefect of Como Province, Franco Scassellati. Jermini had presented himself to Massa as a very wealthy Jew looking to escape into Switzerland. His infiltration led to the arrest of over thirty members of the band and to the Calò and Campi families being taken into custody.

Primo Mazza, the proprietor of the Trattoria Volta in Brunate, organised the expatriation of Jews and others seeking safety over the Swiss border.

The Levi family from Milan were arrested on 4th December. The father Aldo was 45 years old, the mother Elena was 43, their son Italo was 12 and their daughter Elena was a mere 5 years old.

Aldo Levi and his wife, Elena Viterbo

All those mentioned above were detained in one of Como’s prisons before being moved down to Fossoli and placed on Convoy 8.

Como’s Prisons

The increased level of repression and the growing numbers of the ‘state’s enemies’ (Jews, partisans, anti-fascists etc) caused the authorities to supplement the San Donato prison by converting other buildings over for detainees. This was the case with the Comunal gymnasium, the Palestra Mariani, where Ines Figini was held before being deported to slave labour in Mauthausen for supporting a workers’ strike in the Ticosa textile mill. It also applied to the military barracks to the south of the town known as Caserma De Cristoforis. This was partly occupied by the GNR and partly converted into a prison where many of the Jewish prisoners were detained. It was known at the time as the Caserma Monte Santo.

The army barracks – Caserma De Cristoforis – in Como. Citizens had rushed to the barracks in September 1943 to arm themselves after the initial fall of fascism. On the return of Mussolini in September 1943, the barracks were partly occupied by the GNR and used as a prison for detaining Jews.

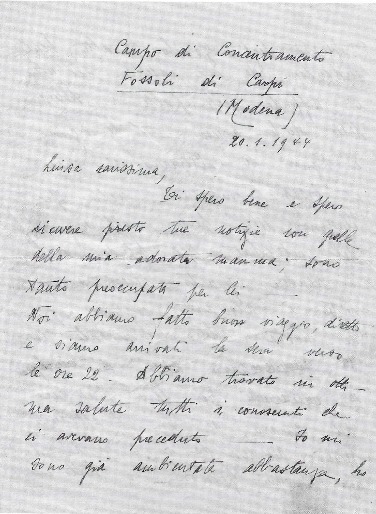

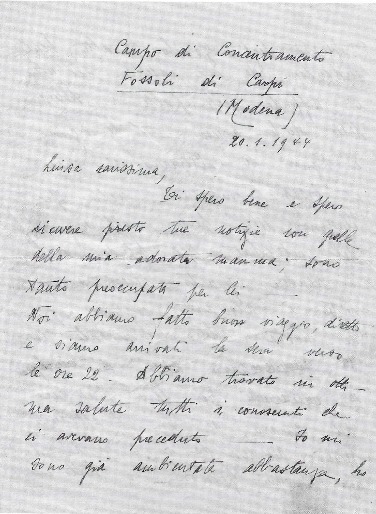

45 year old Olga Fleischer, resident in Milan, had been brought to the Monte Santo Prison along with her 73 year old mother, Ida Goldschmiedt. They had been arrested on 4th December 1943 on arriving at Como’s San Giovanni train station with the idea of finding their way to Bellinzona over the border. A young 18 year old Red Cross nurse called Luisa Colombo befriended Olga during her time in the prison. When Olga’s mother was later released from prison, Luisa did her best to follow up on her welfare keeping Olga informed. When Olga was moved down to Fossoli on January 20th 1944, she kept up a correspondence with Luisa up until the moment she was placed on Convoy 8 a month later.

Letter written by Olga Fleischer to Luisa Colombo from Fossoli detention camp. She writes:Dearest Luisa, I hope you are well and can soon send your news about my adored mother; I am very worried about her. We had a good journey here without changes and arrived in the evening at about 22.00. We have found those others we have met previously to be in excellent health. I have almost got used to my new location

Olga’s mother was initially released due to her age. Many elderly Jews had assumed the state would not act so viciously against the elderly. Unfortunately they were soon disabused. Ida was re-arrested on 14th December, detained yet again in Como prior to being transferred to Fossoli. She would then be put on Convoy 9 and killed on her arrival in Auschwitz.

Luisa Colombo and a nun, Sister Cecilia, befriended another inmate of Monte Santo – the 68 year old Anna Corinna Corinaldi. She was originally from Milan but had more recently moved to Cernobbio in Via Regina 61 to avoid the bombing. The decree passed on 30th November 1943 had finally convinced her that her life was in danger. She attempted to cross over to safety in Switzerland from Tirano in the Valtellina but was arrested there on 13th December. Out of bureaucratic correctness, she was brought back to Como for interrogation and detention. She too was transferred to Fossoli and put on Convoy 8 for Auschwitz on the 22nd February 1944. Whilst in the Monte Santo prison she had gained the help of Sister Cecilia in presenting her case to the state police. Ever hopeful of being freed from Fossoli she had written to Luisa Colombo and referring to Sister Cecilia had stated optimistically “On my return I will seek her out. Dear Signorina, I will never easily forget her, believe me, and I do so hope to meet up with her again in better more serene times. I am at least delighted to have known her.”

Luisa Colombo, the 18 year old Red Cross nurse who befriended and sought to help a number of detainees at the Monte Santo prison

Another elderly lady, Margherita Luzzatto aged 65, wrote a note to Luisa Colombo on 2nd February 1943 from Fossoli stating, “Dear Signorina, I learnt yesterday that my husband has been rearrested in Como and sent to Milan. Did you know? Is there anything you could do?”. Margherita’s husband was Michelangelo Boehm, aged 76, a highly acclaimed technical expert in managing domestic and industrial gas supplies. Husband and wife had tried to cross the Swiss border at Tirano in the Valtellina. They had residence within the Province of Como and so were returned to Como for detention.

Michelangelo wrote the following letter dated 6th January 1944 from Monte Santo Prison to Lorenzo Pozzoli, the Head of State Police in Como: “The undersigned Gr. Uff. Ing. Michelangelo Boehm, son of Benedetto, Italian citizen, born in Treviso on 25 November 1867 to Israeli parents, living in Maggio (Municipality of Cremeno), found here as of now together with his wife, in the absence of his children and other family members, asks to be free to leave this place, temporarily establishing his domicile in a hotel in this city, expecting to return home in May, as soon as freedom is also granted to his wife, who is indisposed […] point out that the wife herself is familiar with the care necessary for her husband and the diet to which he must be subjected.“

Michelangelo was initially released and cared for by the nuns of Valduce Hospital. But Margherita remained in prison until transferred to Fossoli and subsequently placed on Convoy 8 leaving on 22nd February 1944 with destination Auschwitz.

Michelangelo had been freed similarly to the mother of Olga Fleischer, because a police order dated 10th December 1943 amended the general arrest warrants for Jews published ten days earlier by providing an exception for those over seventy or gravely ill. This amendment was however quickly rescinded by the SS Command in Milan meaning that Olga’s mother Ida and Michelangelo found themselves back in Como’s prisons. Michelangelo was subsequently deported to Auschwitz from Milan on the 30th January 1944. He died on arrival at the death camp.

Margherita Luzzatto and Michelangelo Boehm. Photo courtesy of CDEC

Fossoli

The concentration camp in Fossoli in the Province of Modena started life housing allied prisoners of war until the armistice published on September 8th 1943. Once the Nazis had reinstated Mussolini as head of the RSI (Repubblica Socialista Italiana), the fascists set about adapting the camp to house Jews. With the declaration of 30th November calling for the internment of all Jews, Fossoli was quickly expanded with extra barracks built to house entire families such as the those like the Levis, Valebregas, Calòs and Campis arrested in Como.

The camp was run by the RSI until the Nazi SS took it over in March 1944. Prior to that the RSI partnered the Nazis in preparing detainees for transportation to the Nazi death camps. The first convoy departure from Fossoli was Convoy 8 leaving on 22nd February 1944.

In addition to those detainees already mentioned, there were others arrested individually and detained in Como who were to take their place on that first convoy out of the camp. They were:

- Arrigo Levi, aged 61 who had been arrested in Como on 20th December 1943.

- Ada Vitali, aged 57 from Milan, arrested in Tavernerio in December.

- Oddone Pesaro, aged 54 from Milan, arrested in Como in December 1943

The Convoy

We know about the conditions on Convoy 8 because it included two detainees who managed to survive their time in Auschwitz and Birkenau. They were Leonardo De Benedetti, arrested alongside his wife in Lanzo D’Intelvi, and his good friend Primo Levi, the author of ‘If This is a Man’ and the ‘The Periodic Table’. Levi and Leonardo De Benedetti wrote a report together on the conditions in the concentration camps for their Red Army rescuers. Later in 2006 this was published under the name ‘Auschwitz Report’.

From this we know that the convoy transported around 650 prisoners in twelve cattle trucks each housing around 50 deportees. The eldest of the detainees was over 80 and the youngest a three month old baby. The journey took four days with the prisoners being fed bread, jam and cheese along the journey but given no water. To quench their thirst the prisoners had to eat snow whenever the convoy stopped.

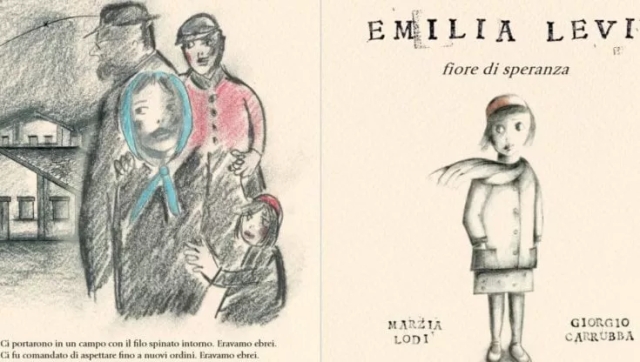

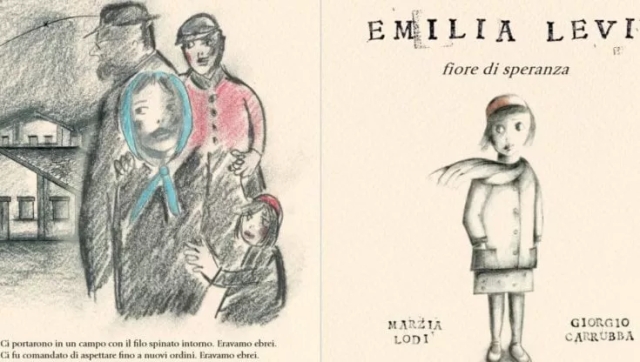

Cover of a picture book recounting the journey of the 5 year old Emilia Levi arrested with her mother and father in Como and transported along with the author Primo Levi to Auschwitz on Convoy 8.

Primo Levi had noted a small five year old girl in his carriage and wrote of her in the first chapter of ‘If This is a Man’ describing her as “A curious, ambitious, cheerful and intelligent little girl who, during the journey in the crowded carriage, her father and mother had managed to bathe in a zinc tub, in warm water that the degenerate German engineer had agreed to pour from the locomotive that dragged us all to our deaths“. This was Emilia Levi, arrested in Como along with her father, mother, and elder brother on the previous 4th December.

The train arrived at Auschwitz at 9.00pm on 26th February.

Arrival at Auschwitz

As soon as the train arrived in Auschwitz, soldiers of the SS armed with pistols and batons cleared the trucks forcing the deportees to leave all luggage behind. They were then divided into three groups as follows:

- 95 young and able men

- 29 young women

- 525 children, elderly and infirm.

A card seeking information on the whereabouts of Jolanda De Benedetti. She had been killed immediately on arriving at Auschwitz on Convoy 8 accompanied by her husband.

This last group was marched straight to the newly installed gas chambers in Birkenau where they were massacred. The victims included Leonardo’s wife, Jolanda. The young men were marched 8 kilometres to Monowitz, a labour camp for the Buna-Werke complex of IG Farbenindustrie set up to produce synthetic rubber. Leonardo and Primo Levi were in this group. IG Farben never managed to produce any synthetic rubber at this plant due to allied air raids but mainly down to constant sabotage by the Polish civilian workers employed there.

Summary

The fate of those referred to in this article, all of whom were arrested in Como and put on Convoy 8, was as follows. Those who died at place and date unknown never managed to return home and died during their captivity:

Leonardo De Benedetti: Survived the holocaust and returned to Turin with his friend Primo Levi and resumed his role as a general practitioner. He died of natural causes in 1983 aged 85. His mother who had managed to pass into Switzerland was to die shortly afterwards.

Jolanda De Benedetti: Killed on arrival at Auschwitz 26th February 1944.

The Bassani family: Father Edgardo survived until 27th April but died after at a place and date unknown, mother Ines died at a place and date unknown, son Franco died after 5th May 1944 at a place and date unknown and daughter Tina died at a place and date unknown.

The Valabrega family: Father Arturo died at Auschwitz 4th April 1944, wife Ida was killed on arrival at Auschwitz 26th February 1943, son Luciano died at Flossenburg 6th April 1945.

The Calò family: Father Emilio was killed on arrival at Auschwitz on 26th February 1943, mother Enrichetta died at a place and date unknown, daughter Rosina died in Bergen Belsen after February 1945, son Giuseppe died after 26th January 1945 at a place and date unknown, uncle Vittorio died at a place and date unknown, aunt Norma died at a place and date unknown.

The Campi family: Father Massimiliano died at a place and date unknown, mother Iris died at a place and date unknown, daughter Lia died at a place and date unknown.

The Levi family: Father Aldo died after March 1945 at a place and date unknown, mother Elena died at a place and date unknown, son Italo was killed on arrival at Auschwitz 26th February 1943, daughter Emilia was also killed on arrival at Auschwitz on 26th February 1943.

Olga Fleischer died at a place and date unknown.

Anna Corinna Corinaldi was killed on arrival at Auschwitz 26th February 1943.

Margherita Luzzatto was killed on arrival at Auschwitz 26th February 1943.

Arrigo Levi, died after Sept 1944 at a place and date unknown.

Ada Vitali, died after 31st March 1944 at a place and date unknown.

Oddone Pesaro was killed on arrival at Auschwitz on 26th February 1943.

The atrocity of the Holocaust and the impact of such a massive scale of genocide is hard now to imagine. Out of the 6 to 7 million victims across Europe, I have focussed here on a very specific group that were all arrested in Como over December 1943 seeking to show how in this small corner of the European conflict, the diverse backgrounds of these victims led them on the same journey and to the same fate due purely to their shared ethnicity. The enormity of where racism can lead us must surely never be forgotten.

Wreath at the Memorial to Resistance in Como laid by ANPI – the National Association of Italian Partisans. Up to 2000 young Jews joined the Italian partisans, predominantly choosing Brigades of Giustizia e Liberta or the Garibaldini.

Sources

Rosaria Marchesi, Como Ultima Uscita, 2004 Nodo Libri

Liliana Picciotto, Il Libro della Memoria, 2002 Mursia

Francesco Scomazzon, “Maledetti Figli di Giuda, Vi Prenderemo”, 2005, EsseZeta

CDEC (Centro di Documentazione Ebraica) Digital Library

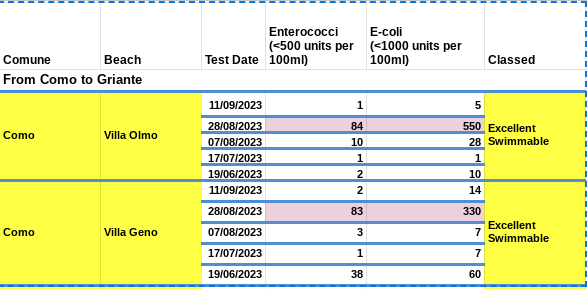

This table shows the ranking of all the beaches and lidos tested in our area. The figures in the right hand column are simply the sum of all the data collected over the five occasions during the swimming season. For the details, please go to the Portale Acqua site.

This table shows the ranking of all the beaches and lidos tested in our area. The figures in the right hand column are simply the sum of all the data collected over the five occasions during the swimming season. For the details, please go to the Portale Acqua site.

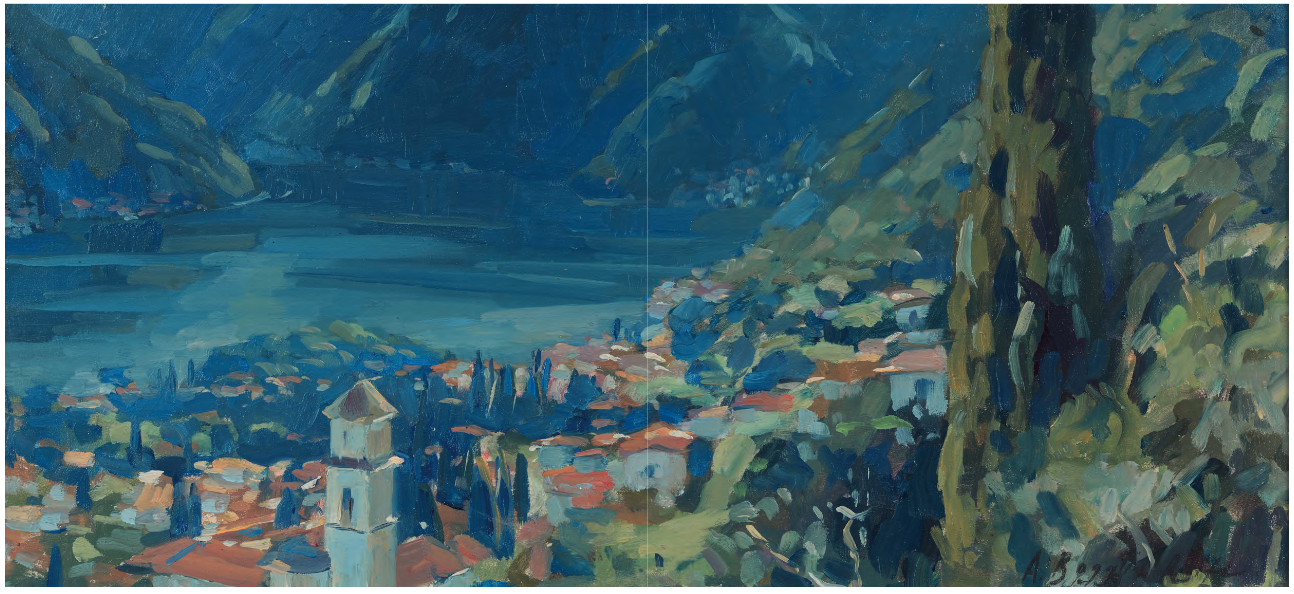

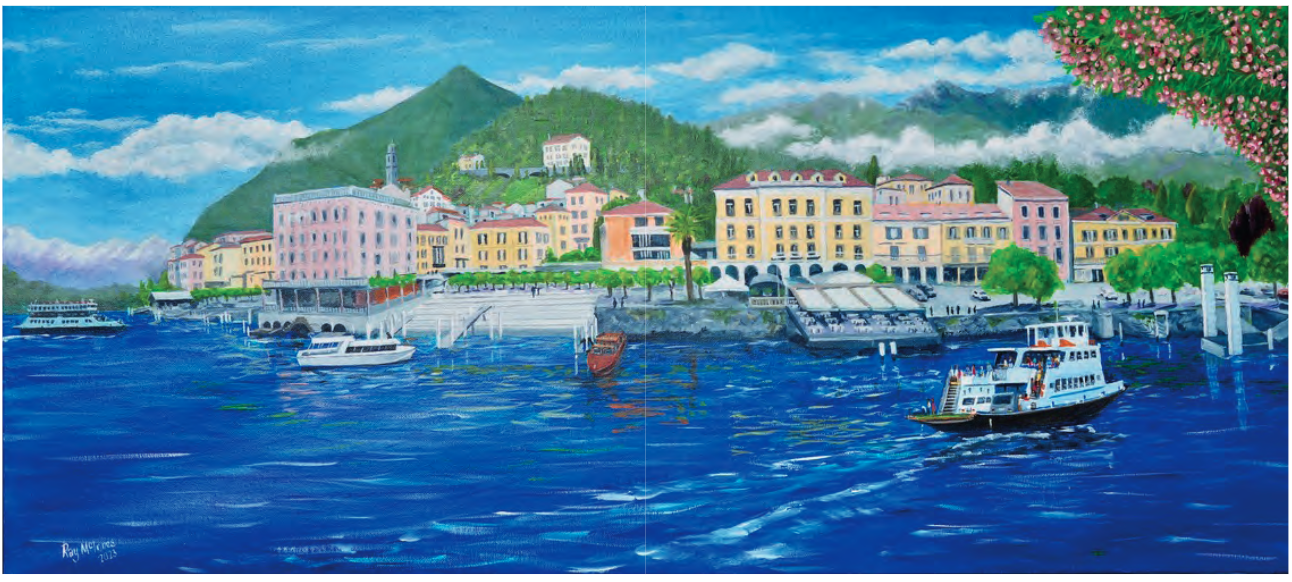

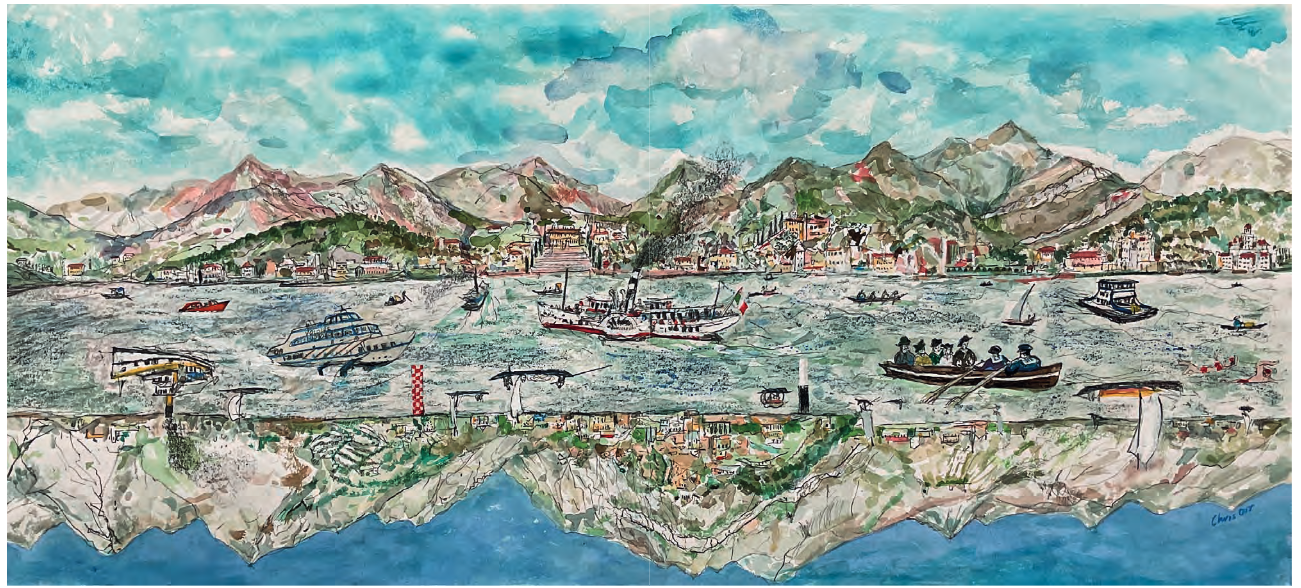

Over recent centuries Lake Como has gained increasing popularity as a holiday and travel destination. It comes as no surprise that the sparkling lake and the majestic mountains that surround it find themselves used as the setting in a wide selection of novels. On the one hand, Lake Como is commonly perceived as a romantic location and so is used as a fitting backdrop to amorous tales. Yet its location selected for the fascist era’s endgame confirmed its dramatic credentials for setting historical narratives. And the very depth of the lake beneath its shimmering superficiality symbolises the duplicity of darkness and danger for mystery, murder and intrigue.

Over recent centuries Lake Como has gained increasing popularity as a holiday and travel destination. It comes as no surprise that the sparkling lake and the majestic mountains that surround it find themselves used as the setting in a wide selection of novels. On the one hand, Lake Como is commonly perceived as a romantic location and so is used as a fitting backdrop to amorous tales. Yet its location selected for the fascist era’s endgame confirmed its dramatic credentials for setting historical narratives. And the very depth of the lake beneath its shimmering superficiality symbolises the duplicity of darkness and danger for mystery, murder and intrigue.